Kategorie: Background in English

At the Movies with James Baldwin

The writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin wrote about racism in US society and the movies. "If Beale Street Could Talk", the first adaptation of a Baldwin novel, is heavily influenced by his legacy.

By the age of about 13, James Baldwin was already a regular visitor to the movie theater. That was in the 1930s, when talkies had established themselves and the "golden era" of Hollywood's commercial success was beginning. As we learn about Baldwin in the essay film Zum Filmarchiv: "I Am Not Your Negro" (USA 2017), he was usually taken to the theater or cinema by his white teacher Orilla Miller (known as "Bill"). She wanted to promote and encourage this inquisitive boy. But on the screen, Baldwin could not see the life led by himself and his family: African-Americans did not exist in these films – or when they did, merely in small supporting roles, as servants of the main characters. "Heroes, as I far as I could then see, were white," he would later write in his cinematic essay The Devil Finds Work (1976), "and not merely because of the movies but because of the land in which I lived, of which movies were simply a reflection."

Hollywood Movies in the Eyes of a Black Critic

Baldwin was born in 1924 in New York. As the eldest of nine children born into poverty, he grew up in the African-American district of Harlem, known back then as a "ghetto" even by its residents. He said the only (white) actress at the time who reminded him of a black woman and hence a piece of reality was Sylvia Sidney. Among the films Sidney acted in were movies made by the German director Fritz Lang, such as "Fury" (USA 1936) or "You Only Live Once" (USA 1937), in which she played women with tragic stories of suffering: "She was always being beaten up, victimized, weeping." In the book "The Devil Finds Work", which is frequently quoted in "I Am Not Your Negro", Baldwin anticipated today's debate about racism in film more than 40 years ago. He demonstrates how the power structures of society are inscribed in cinematic narratives; how images contain discriminating or clichéd representations of black people, even when they are supposed to portray harmless love, crime or adventure stories.

He is especially critical of some of the first Hollywood movies, which feature African-American actors such as Sidney Poitier and which portray the conflict between blacks and whites in a "well-meaning" (Baldwin) way. The first of these films, such as "The Defiant Ones" (Stanley Kramer, USA 1958) or "In the Heat of the Night" (Norman Jewison, USA 1967), were shot exclusively by white, politically liberal directors. Baldwin sees Poitier, the first African-American Oscar®-winner for best actor ("Lilies of the Field", Ralph Nelson, USA 1963), as a performer of the "black experience" – who usually struggled with being cast in naive, non-credible stories. One example: in "The Defiant Ones", a white and a black prisoner overcome their mutual hatred – as if the hatred of a white racist, against a background of slavery and ongoing injustice, could simply be forgiven. In the end, Poitier's character jumps off a train that would have rescued him, so as not to leave his comrade alone at the mercy of police. According to Baldwin, white people in the audience applauded while black people in Harlem shouted at the screen: "Get back on the train, you fool!"

The Mediating Voice of the Civil Rights Movement

Baldwin himself spent his entire life moving between these two worlds. He graduated from a largely white high school in the Bronx and continued to live in Harlem, before he moved to France in 1948; while there, he continued to write about the situation of black people in the US. After a temporary return in the 1960s, he became one of the leading intellectuals of the Civil Rights Movement, appearing on chat shows and meeting politicians. In 1963 he was part of an African-American delegation that lobbied attorney general Robert Kennedy for civil rights; Kennedy subsequently ordered the FBI to keep an eye on his guests. Baldwin was friends with prominent black activists and artists such as Nina Simone but he also made friends with white celebrities such as Marlon Brando.

Available for streaming in the media center on bpb.de:

the essay film Zum externen Inhalt: "I Am Not Your Negro" (öffnet im neuen Tab)

He remained very much an individual voice as an author, always writing from a subjective, highly-involved perspective, whether fiction or non-fiction. In The Fire Next Time (1963) he addressed a young nephew with the observation: "You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being." This form of autobiographical essay influenced many writers, not least the current American intellectual Ta-Nehisi Coates. Despite his dark view of the chances, rights, and living conditions of the black minority, Baldwin still sees a way out through dialogue. He rejects a separate "black nation" on US territory, as propagated by his contemporary Malcolm X and his militant "Nation of Islam." At the same time, however, he upends the notion that African-Americans must be integrated into society in order to partake in it, arguing that it is not black America but white America that needed to be accepted and integrated, so that it could face up to its deep-seated fears and history of violence.

In the Spirit of Baldwin: The Adaptation "If Beale Street Could Talk"

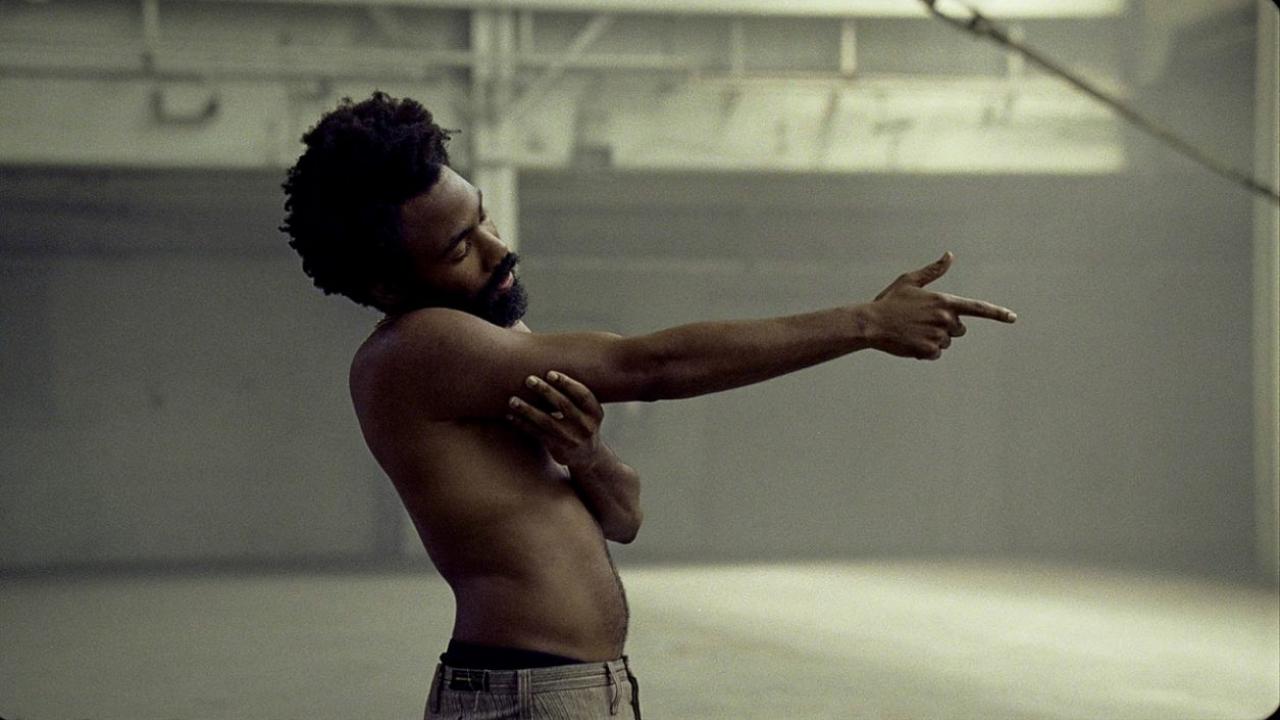

Following his Oscar®-winning Zum Filmarchiv: "Moonlight" (USA 2016), Barry Jenkins has directed the first adaptation of a novel by James Baldwin, Zum Filmarchiv: "If Beale Street Could Talk" (USA 2018). This story of a young couple, Tish and Fonny, in 1970s New York, tells in equal parts of arbitrary police actions and structural racism, and of love and solidarity in the African-American community. Jenkins shows great respect for the original and stays true to the novel "If Beale Street Could Talk" (1974): the film, too, features a voice-over narrative from Tish's perspective and many passages are taken over word for word. The cast of characters and the complicated interweaving of flashbacks are also replicated. Small but significant changes in the opening and closing scenes and the always somewhat extravagant portrayal of the two lovers give the film a more optimistic tone.

"There is a lack of black stories," according to Jenkins. "If Beale Street Could Talk" therefore also shows an awareness of Hollywood's style of pictures, so bitterly criticized by Baldwin. Jazz, soul and blues on the soundtrack, stylized close-ups of faces, actors looking straight into the camera – it is almost as if the film were saying: this is a black story about America. Or in Baldwin's own words: "The story of the Negro in America is the story of America."

Weiterführende Links

- External Link Bpb Media Center: Essay film "I Am Not Your Negro"

- External Link Books by James Baldwin

- External Link "The Devil Finds Work" by James Baldwin

- External Link APuZ magazine: Black America (german)

- External Link bpb edition: "Between the world and me" by Ta-Nehisi Coates

- External Link bpb edition: "We Were Eight Years in Power" by Ta-Nehisi Coates